In my recent book, Kidnapping the Enemy: The Special Operations to Capture Generals Charles Lee and Richard Prescott (Westholme Publishing, 2013), I focus on two of the outstanding kidnappings of the Revolutionary War. The first was the stunning capture of Major General Charles Lee, second-in-command of the Continental army, by Lieutenant Colonel William Harcourt and a party of British dragoons on December 13, 1776. Second was the perhaps even more incredible capture of Major General Richard Prescott, the commander of British troops in Newport, Rhode Island, by state troops led by Lieutenant Colonel William Barton. Barton seized Prescott so the Americans would have a British officer of the same rank to exchange for Lee.

There were other attempts during the Revolutionary War to kidnap high-ranking military officers and government officials. George Washington himself applauded and supported such efforts undertaken by the American army. Referring to a bid to capture British commander-in-chief Henry Clinton in 1778, he wrote, “I think it one of . . . the most desirable and honorable things imaginable taking him prisoner.”[1] In the winter of 1779-1780, Washington himself was the target of a serious attempt to capture him at his isolated headquarters at Morristown, as nicely summarized by Benjamin Huggins in Journal of the American Revolution (“Raid Across the Ice: the British Operation to Capture Washington,” Dec. 17, 2013).

By late March of 1782, after the stunning American victory at Yorktown, the tide of war had turned in favor of the Americans (and French), and military operations were winding down. Nevertheless, Washington approved an operation to kidnap King George III’s son, Prince William Henry, and Admiral Robert Digby, both of whom were visiting British-occupied New York City. It is not clear what the American commander-in-chief intended to do with the young prince. Normally, a high ranking officer was exchanged for someone of equal rank, but obviously the Americans did not have a royal counterpart being held captive by the British who could be exchanged on a one-for-one basis. Washington probably thought that William Henry could be exchanged for numerous American captive prisoners, still rotting in fetid conditions on board the notorious Jersey British prison ship off of Brooklyn.

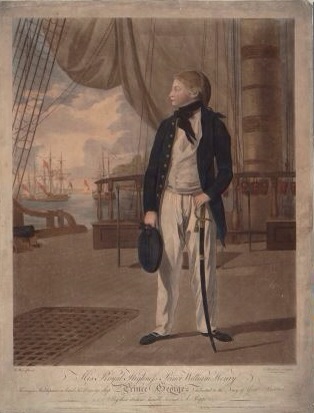

The prince, third in line to the British throne when he arrived in New York City on September 26, 1781, was the “first of royal lineage” to visit America.[2] He was, according to Loyalist William Smith, “received by Sir Henry Clinton, the Governor, and a crowd behind Kennedy’s house on the North [Hudson] River.”[3] Archibald Kennedy’s house, at Number One Broadway at the southern tip of Manhattan Island, served as the headquarters of General Clinton, commander-in-chief of British forces in North America.

Then a seventeen-year-old midshipman on Digby’s flagship, HMS Prince George, the prince quickly endeared himself to locals with his boyish charm. A London magazine later recalled of his visit:

One of his favorite resorts was a fresh-water lake in the vicinity of the city, which presented a frozen sheet of many acres, and was thronged by the younger part of the population for the amusement of skating. As the Prince was unskilled in that exercise, he would sit in a chair fixed on runners, which was pushed forward with great velocity by a skating attendant, while a crowd of officers environed him, and the youthful multitude made the air ring with their shouts for Prince William Henry.[4]

The plan to kidnap Prince William Henry, Admiral Digby, and other notables had been proposed in late March by Colonel Matthias Ogden of the 1st New Jersey Continentals, whose regiment was then based in New Jersey.[5] Ogden, who was raised in the same Elizabethtown household as Aaron Burr and had attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), had demonstrated his courage during the failed assault on lower Quebec on December 31, 1775. Ogden’s idea immediately captivated the commander-in-chief. “The spirit and enterprise so conspicuous in your plan for surprising in their quarters, and bringing off, Prince William Henry and Admiral Digby merits applause, and you have my authority to make the attempt in any manner, and at such a time, as your own judgment should direct,” Washington wrote on March 28, 1782.[6] The general did warn “against offering insult or indignity to the persons of the Prince, or Admiral, should you be so fortunate as to capture them,” and recommended that Ogden “impress the propriety of such conduct upon the party you command.”[7]

Ogden’s plan called for him to surprise both the prince and the admiral in their city quarters and quickly hustle them off Manhattan Island. His force would include a captain, a subaltern, three sergeants, and thirty-six other soldiers. In four whaleboats equipped with muffled oars, Ogden’s well-armed men would embark from the New Jersey shore on a rainy night, pass around the tip of Manhattan to enter the East River, and land on the east side of lower Manhattan (near the current South Street Seaport) at about 9:30 p.m., at a spot not far from Hanover Square, the location of their targets’ quarters. (Hanover Square, then the heart of the downtown district, is where the current Pearl Street and Wall Street meet.)

The operation’s leader had solid intelligence about several guard posts that his party wanted to avoid, but might have to confront, as he explained to Washington:

The Prince’s quarters are in Hanover Square in the large house of Bateman’s [Beekman’s]. It has two sentinels from the British 40th Regiment quartered in Lord Stirling’s house on Broad Street, 200 yards from the scene of the action. The main guard, consisting of a captain and forty men, is posted at City Hall; a sergeant and twelve men, at the head of the old slip; and a sergeant and twelve men, opposite the Coffee House. These are the nearest men in arms and must be guarded against. The place of landing to be at Coenties Market, which is between the two sergeants’ guards.[8]

Ogden did not reveal to his commander one important fact, probably because Washington was already aware: at this time, downtown New York City was packed with more than 1,500 British and Hessian soldiers, not to mention Loyalist irregulars and sailors on temporary leave in the port.[9]

Leaving some men to guard the boats, Lieutenant Colonel Ogden and the balance of his force would proceed to the house, force its doors with “two axes and two crow bars” and secure the prince and admiral, as well as any “young noblemen, etc. . .” who were also present. In returning to the boats, some of his men armed with guns and bayonets were to precede the prisoners, with others to follow at half-gunshot distance, to give a front to the enemy until all were embarked. In his written plan for the mission, Ogden noted the need for “two or three dark lanterns,” as well as some “sailor’s clothing.”[10] Presumably, he meant garb typically worn by sailors on private commercial vessels or privateers, and not the regulation clothing of British sailors. Any man caught in disguise would risk being hanged as a spy if caught by the British.

In the end, it did not matter. The operation to kidnap the prince and the admiral was never attempted. Washington received the following report, dated March 23, 1782, from one of his spies in New York City:

Great seems to be their apprehensions here. About a fortnight ago a number of flat-boats were discovered by a sentinel from the bank of the river (Hudson), which are said to have been intended to fire the suburbs, and in the height of the conflagration to make a descent on the lower part of the city, and wrest from our embraces his excellency Sir H. Clinton, Prince William Henry, and several other illustrious personages—since which great precautions have been taken for the security of those gentlemen, by augmenting the guards, and to render their persons as little exposed as possible.[11]

Washington quickly warned Ogden. “I received information that the sentries at the doors of Sir Henry Clinton’s quarters were doubled at eight o’clock every night from the apprehension of an attempt to surprise him in them,” he wrote on April 2. “If this be true, it is more than probable the same precaution extends to other personages in the City of New York, a circumstance I thought it proper for you to be advertised of.”[12] The precautions taken by British forces probably convinced Ogden to scuttle his operation.

A half-century later, in 1831, Louis McLane, then the U.S. ambassador to Great Britain, showed a copy of Washington’s March 28, 1782, letter addressed to Lieutenant Colonel Ogden to King William IV—the former Prince William Henry. “I am obliged to General Washington for his humanity, but I’m damned glad I did not give him an opportunity of exercising it towards me,” the king reportedly remarked.[13] Washington’s and Ogden’s correspondence, copies of which were provided by Ogden’s son, was published in England’s Athenaeum magazine in May of that year and created quite a stir among His Royal Highness’s subjects.

An early and sympathetic British biographer of the king was not so charitable, writing of Washington, “the part in which he took in the kidnapping of Prince William will always stand in record against him, as one of the most despicable acts of his life.”[14] But as noted above, it was probably the case that Washington wanted to use Prince William Henry to barter for the release of American prisoners. In June of 1782, Washington sent a note to Admiral Digby, asking him to do what he could to help to relieve the sufferings of American captives held on British prison ships.[15]

Still, if the attempt to abduct Prince William Henry had succeeded, one wonders if it might have backfired. The outrage in London might have led to a groundswell of support for continuing the war and a renewed effort to subdue or punish Washington’s army. As it turned out, the attempt was not made, and an August 2, 1782 letter sent by Admiral Digby and Sir Guy Carleton to Washington contained the first news that Great Britain had commenced negotiations in Paris for an end the war.[16]

King William IV did not have a distinguished or a long reign. While important reforms took place during his reign, they likely would have occurred in any event. He had ten children, none from his wife. He reigned until 1837, when he died and a young Victoria became queen.

[1] G. Washington to S. Parsons, March 5, 1778, in Chase, Philander et al. (eds.), The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 14 (Charlottesville, VA, University of Virginia Press, 2004), 72.

[2] Pennsylvania Packet, Oct. 4, 1781 (“first of royal lineage”).

[3] W. Smith Diary Entry, Sept. 26, 1781, in Sabine, William H. W. (ed.), Historical Memoirs of William Smith, vol. 2 (New York, NY, W.H.W. Sabine, 1956), 447. Prince William had arrived on September 24 at Sandy Hook, New Jersey on board Digby’s flagship, HMS Prince George, accompanied by two other warships. Diary Entry, Sept. 24, 1781, in id., 446; see also Rivington’s Royal Gazette, Sept. 26, 1781.

[4] The Athenaeum, vol. 186 (May 21, 1831), 321.

[5] M. Ogden to G. Washington, March (probably on or around 26), 1782, George Washington Papers, microfilm reel 83, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[6] G. Washington to M. Ogden, March 28, 1782, in Fitzpatrick, John C. (ed.), The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745-1799, vol. 24 (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1938), 91.

[7] G. Washington to M. Ogden, March 28, 1782, in Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington, 91.

[8] M. Ogden to G. Washington, March (probably on or around 26), 1782, George Washington Papers, microfilm reel 83, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. Parts of this letter were quoted (and slightly altered from the original) in The Athenaeum, vol. 186 (May 21, 1831), 321-22, but the editors did not realize that the quotes were from Ogden’s initial March 1782 letter to Washington.

It appears Ogden mistakenly reported that Prince William Henry was then residing at Bateman’s house, which the author has not identified. The Prince and Admiral Digby stayed at the Gerardus Beekman mansion on Hanover Square, which had been taken over by British naval officers. See Heath, William, Heath’s Memoirs of the American War (Boston, MA: Thomas and E.T. Co., 1798), 418; Lossing, Benson J., The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution, vol. 2 (New Rochelle, NY: Caratzas Bros. 1976) (originally published in 1850), 629, n. 1; Booth, Mary, History of the City of New York from Its Earliest Settlement to the Present Time (New York, NY: W.R.C. Clark & Meeker, 1859), 511. The current India House, one of the few pre-Civil War buildings left in New York City, is at One Hanover Square. The reference to Lord Stirling is to Major General William Alexander Stirling of the Continental army—he stayed at a house on Broad Street when the main Continental army occupied Manhattan Island in 1776. Coenties Market, also called the Great Fish Market, was at Coenties Slip at Pearl Street on the East River. The slip was filled to South Street about 1880. Only the apex, between Pearl and Water Streets, retains its historic name. Old Slip, the city’s first slip, was known as Old Slip by 1730. It was filled to South Street in 1834 but the filled in area currently retains the name. See the website “Old Streets of New York,” at www.oldstreets.com.

[9] The Estimate of the Enemy’s Force in New York and Its Dependencies with the Disposition of It, February 1782, in George Washington Papers, microfilm reel 83, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, with Colonel Ogden’s name on it, indicated that the following units were stationed at the “Garrison of the City” of New York: British 40th Regiment, 200 soldiers; one battalion of Hessians, 200 soldiers; and 2 battalions of Hessian grenadiers, 1,100 soldiers. See also A List of the Enemy’s Corps in New York and Its Dependencies with the Distribution of Them, February 1782, in George Washington Papers, microfilm reel 83, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. (“City of New York”: British 40th Regiment; four battalions of Hessian grenadiers; Hessian Landgrave Regiment; and the Hessian Knyphausen Regiment).

[10] M. Ogden to G. Washington, March (probably on or around 25), 1782, George Washington Papers, microfilm reel 83, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[11] Intelligence Report sent to G. Washington, March 23, 1782, quoted in The Athenaeum, vol. 186 (May 21, 1831), 322. The Athenaeum indicates that the handwritten report was taken from a fragment of a letter written by Washington to Ogden, but it appears from its language that it was written by the secret agent in New York for Washington’s eyes. The Athenaeum likely received handwritten copies of the original correspondence, not the originals themselves. The Athenaeum’s report was republished in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (London) vol. 17, no. 492 (June 4, 1831), 380-81.

[12] G. Washington to M. Ogden, April 2, 1782, in Fitzpatrick (ed.), Washington Writings, vol. 24, 99-100.

[13] Quoted in Fitzpatrick (ed.), Washington Writings, vol. 24, 91, n. 45. John C. Fitzpatrick, editor of Washington Writings, wrote in note 45, accompanying Washington’s March 28 letter: “On the letter sent, which was sold at auction in 1920, is an endorsement by Robert Gilmor that he secured this letter from Louis McLane, then United States Minister to Great Britain, who at one time showed it to the King (formerly Prince William Henry and then William IV, of Great Britain), who had remarked: ‘I am obliged to General Washington for his humanity, but I’m damn’d glad I did not give him an opportunity of exercising it towards me.’” See also Stokes, I. N. Phelps, The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498-1909 . . . , vol. 5 (New York, NY: Robert H. Dodd, 1926), 1145 (quoting from same auction catalogue).

[14] Huish, Rober, The History of the Life and Reign of William the Fourth, the Reform Monarch of England (London: William Emans, 1837), 108. Huish continued, “That the capture of Prince William would have been advantageous to the Americans there is no doubt, but on the other hand, the hazard with which the undertaking was attended, was perhaps greater than the advantage which would have been derived from the possession of his person.”

[15] G. Washington to R. Digby, June 5, 1782, in Fitzpatrick (ed.), Washington Writings, vol. 24, 315-16.

[16] G. Washington to N. Greene, Aug. 6, 1786, in ibid., 471 (quoting from Aug. 2 letter); see also G. Washington to President of Congress, Aug. 5, 1782, in id. (forwarding letter to Congress), 466-66 and G. Washington to G. Carleton and R. Digby, Aug. 5, 1782, in id., 468-69 (confirming receipt of letter).

3 Comments

Having searched without success for detailed information on the web about the plot to kidnap Prince William, I was thrilled to stumble upon your site this morning!

Thanks for sharing it! 🙂

This seems almost too hare-brained to believe but wars tend to call for desperate measures. Movie buffs may recall The Dirty Dozen and The Cockleshell Heroes, both based on similar ‘forlorn hope’ enterprises of WWII. I enjoyed the article but the question hanging in the air for me is ‘who was responsible for those flat-bottomed boats that made the British more wary?’