As a near-life-long New York resident and “struggling actor,” it is always a pleasure to see the ever-present throngs of theatre-goers throughout the City. Theatre has for well over a century been recognized as an American art form, especially the musicals that so dominate Broadway. Yet while common today, the theatre had a far different, and darker, connotation in Revolutionary New York.

“Freedom” and “liberty” are words so often applied to American government, culture and society during the Revolutionary period that it is sometimes easy to forget that late-eighteenth-century folk and us twenty-first-century folk define those words very differently. The ubiquity of slavery, property limits on voting rights and the subservient position of women all give pause to modern ears when Revolutionary America is discussed as a beacon of liberty. But these common examples of liberty deferred are not the only ones.

While today the theatre is seen as a perfectly acceptable form of both art and commerce, as well as a patriotic expression of American freedoms, to many members of the Continental Congress it was an unpatriotic and unacceptable element of society, so much so that one of Congress’ first acts was the banning of theatre! Today such a drastic and heavy-handed move would be the complete opposite of “liberty;” to Congress then, it was seen as a national necessity.

In October 1774, the First Continental Congress passed the Articles of Association, which banned all trade with Britain until its grievances were met. While most of the articles dealt with trade specifically and the mechanics of the Articles’ enforcement, Article 8 stated,

We will, in our several stations, promote economy, frugality and industry, and promote agriculture, arts and the manufactures of this country, especially that of wool; and we will discountenance and discourage every species of extravagance and dissipation, especially all horse-racing, all kinds of gaming, cock-fighting, exhibitions of shows , plays and other expensive diversions and entertainments.[1] [emphasis mine]

Through the Association, Congress had placed the theatre on the same low moral plane as gambling or animal fighting – to be discouraged through the Articles’ communal enforcement scheme. To a modern patron or practitioner of the stage, Congress’s act seems just as tyrannical as any taxation without representation!

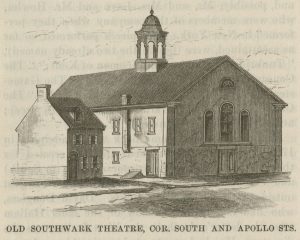

There was certainly enough of a theatrical presence by 1774 to provoke the Articles, and the Association’s Committees of Inspection ensured compliance. Lewis Hallam and David Douglass’ “American Company” of actors (renamed from the “London Company of Comedians” in response to the Stamp Act in 1765) had toured the colonies with popular classic British plays, performing in specially-built playhouses in America’s largest cities: the John Street Theatre in New York, the Southwark Theatre in Philadelphia, Church Street Theatre in Charleston, the West Street Theatre in Annapolis, and the Murray-Kean Theatre in Williamsburg. Upon learning of Congress’ declaration, these playhouses were all left empty. The “American Company” left America for Jamaica upon hearing of the ban in December 1774.[2]

There was certainly enough of a theatrical presence by 1774 to provoke the Articles, and the Association’s Committees of Inspection ensured compliance. Lewis Hallam and David Douglass’ “American Company” of actors (renamed from the “London Company of Comedians” in response to the Stamp Act in 1765) had toured the colonies with popular classic British plays, performing in specially-built playhouses in America’s largest cities: the John Street Theatre in New York, the Southwark Theatre in Philadelphia, Church Street Theatre in Charleston, the West Street Theatre in Annapolis, and the Murray-Kean Theatre in Williamsburg. Upon learning of Congress’ declaration, these playhouses were all left empty. The “American Company” left America for Jamaica upon hearing of the ban in December 1774.[2]

Yet despite this initial widespread compliance, opposition to the Articles was fierce among Loyalists. Influential New York printer James Rivington decried Congress’ behavioral pronouncements as tyrannical and hypocritical in his screed The Poor Man’s Advice to his Poor Neighbors, saying the of Congressman,

They’ll ride in coach and chariot fine,

and go to ball and play,

when we’ve not werewithal to dine,

Tho’ we work hard all day.…

Rare sons of freedom this Congress

So just as they think right,

We are to eat – drink – frolick – dress;

Pray, masters, may we s[hit]e[3]

His Poor Man’s Advice was more concerned with material goods; Rivington also published opposition in the more theatrical form of a dialogue pamphlet, though its exact author is listed as “Mary V.V.,” titled A Dialogue Between a Southern Delegate and his Spouse on His Return from the Grand Continental Congress. The piece is filled with generic romantic humor, ribbing at foolish husbands assembling like gossiping wives, and the lethal folly of rebellion, but this final exchange is telling. After receiving a haranguing from his wife declaring her fear for his safety after passing such treasonous acts as the Association, he says

Husband

You’ve been heating your Brain, with Romances and Plays,

Such Rant and Bombast I never heard in my Days.Wife

Were your new-fangled Doctrines, as modest and true,

‘twould be well for yourselves and your poor Country, too:…

Let’s return to ourselves, if you’ve Eyes, you will see

Your Association big with rank Tyranny.…

You have read a great deal, – with patient Reflection,

Consider one Moment, your Courts of Inspection:…

In all the Records of the most slavish Nation,

You’ll not find an instance of such Usurpation.[4]

The Husband’s complaint may fit with the humorous banter of the rest of the piece, but considering that his Congress had just condemned such “Romances and Plays,” his words bear an ideological slant as well as a purely patriarchal one: plays are a threat to his own power in the household as well as Congress’s across America. The Wife’s response speaks to how effective plays can be: if only Congress’s doctrines were as “modest and true” as plays, they would avoid the “tyranny” and “usurpation” the Association demanded through its behavioral codes and enforcement. In Dialogue, we can see an attempt at defending the theatre using its own language, but a true theatrical professional would later make the point most clearly.

Rivington’s and “Mary’s” pamphlets did cause quite a stir amongst loyalists – James Madison even mentions Dialogue as an example of the force of New York’s opposition.[5] However it was not until December 1775 that Congress’s ban on theatre would be attacked from the stage itself. By that time the war had begun, with Boston under British military control but under siege by the Continental Army. One of the British Major Generals, John Burgoyne, was a playwright himself, having written the comedy Maid of the Oaks in London in 1774. An outspoken opponent of Congress and American demands prior to the war, he found Congress’s ban, as well as Boston’s particular hostility to the theatre, proof of the Revolutionaries’ perfidy.[6] So as the siege began, he had town center Faneuil Hall turned into a playhouse operated by army officers. One of the known productions was Zara by Aaron Hill, a play about religious intolerance during the crusades. In his specially-written prologue to Zara, performed by Francis, Lord Rawdon, Burgoyne makes his views on the American ban on theatre crystal clear:

In Britain once, (it stains th’historic page)

Freedom was vital struck by party rage:

Cromwell the fever watch’d, the knife supplied,

She madden’d and by suicide she died.

Amidst the groans sank every liberal art

Which polish’d life or humaniz’d the heart

Then sunk the Stage, quell’d by the Bigot Roar

Truth fled with Sense & Shakespear charm’d no more.

To sooth the times too much resembling those,

And lull the care-tir’d thought this stage arose;…

Say then Ye Boston Prudes, if Prudes there Are

Is this A Task unworthy of the Fair?

Shall Form, Decorum Piety Refuse

A Call on Beauty to Conduct the Muse?

Perish the Narrow thought, the Slanderous tongue

Where the Heart’s Right, the Action Can’t be wrong[7]

Burgoyne’s prologue makes the connection between Congress’s ban and the ban passed during the English Civil War over a century earlier in the 1640s. To him and his supporters, both were acts of tyranny by an assembly of grasping radicals wishing to make society in its own image, and both would eventually be crushed, with the “freedom” of the “stage” returning.

Burgoyne may have had a point about comparing the Americans of 1774 with the Parliamentarians of 1642. On September 2 of that latter year, Parliament, citing the threat of Civil War and divine need for solemnity, banned theatrical performances, declaring that

While these sad Causes and Set-times of Humiliation do continue, public Stage-Plays shall cease and be forborn. Instead of which, are recommended to the People of this Land, the profitable and seasonable Considerations of Repentance, Reconciliation and Peace with God, which probably may produce outward Peace and Prosperity, and bring again Times of Joy and Gladness to these Nations.[8]

This first religious ban on plays proved ineffective, so a second act was passed in 1648, this one far more forceful and detailed, stating

Whereas the Acts of Stage-Playes, Interludes, and common Playes, condemned by ancient Heathens, and much less to be tolerated amongst Professors of the Christian Religion is the occasion of many and sundry great vices and disorders, tending to the high provocation of Gods wrath and displeasure, which lies heavy upon this Kingdom, and to the disturbance of the peace thereof… all Stage-players and Players of Interludes and common Playes, are hereby declared to be … Rogues.[9]

The act would further detail how theatre buildings were to be dismantled and performers and audience members were to be sentenced and punished. These harsh proscriptions from the seventeenth-century Parliament would give a theatre artist like Burgoyne great pause, and one could see the Continental Congress’s Association taking a similar path. However, distinctions should be made between these English Civil War laws, which were concerned with religion and public morality in a relatively homogenous nation, and the later Association, which dealt with a completely different set of issues and challenges posed by the theatre.

Why, then, would Congress “discountenance and discourage” “exhibitions of shows” and “plays”?

Historians of the subject[10] have noted the lack of sources that directly answer this question: we do not know of the specifics of any particular Congressman’s position on Article 8. Indeed, many colonies passed injunctions against theatrical performances using similar justifications of immorality through the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. These bans were primarily in those colonies founded for religious reasons: Puritan Massachusetts and Quaker Pennsylvania in 1699. However, as the eighteenth century progressed, economic concerns aligned with religious ones. Theatre may have been a simple curiosity to be purged in the 1690s, but by the 1730s, 40s and definitely 50s, the acting companies of Walter Murray and Thomas Kean and Lewis Hallam and David Douglass, fueled by their playhouses, had become economic forces. During the times of economic distress caused by the colonial wars, spending money at the playhouse came to be seen as completely wasteful: after all, the money would go to itinerant, immoral foreign actors rather than a local business like inns or taverns, continuing the economic slump. That theatre came to be associated with the elite did not help its popularity.[11]

These rising forces of religious and economic opposition took on a nationalist air as relations between the colonies and Britain deteriorated throughout the 1760s. Was it not shameful that the elites of the colonies, spurred on by the poor who did not know better, spent their money on British actors performing British plays which would promote British values? The extent to which theatre had become politicized was seen in May 1766 when the New York Sons of Liberty, upon hearing of the repeal of the hated Stamp Act, attacked and destroyed the Chapel Street Theatre as a symbol of British oppression, severely beating a cross-dressing actor and killing a small child.[12] It is the desire for proper morality, frugality and what would become national pride that inspired an America-wide boycott of theatre.

The Puritans in 1642 banned theatre out of fear of moral looseness. While that certainly was a factor in the Association ban in 1774, it was not the only one. The ban on theatre in 1774 was part of a larger program of economic dissociation from Britain to promote American production and trade while hurting Britain’s. Theatre was considered a British trade commodity – a cultural one; with the ban Congress could hurt British industry and national pride, save Americans money and gird them for war, and promote a national moral code all at once!

However, opposition to the theatre ban soon grew from an unexpected source: the Continental Army. In April and May 1778, George Washington approved a series of performances by officers of the Continental Army in Valley Forge outside Philadelphia, most notably Joseph Addison’s Cato, a play largely concerned with the defeat of tyranny (here represented by Caesar) by the forces of liberty (Cato). Why would Washington act in such defiance of Congress’ wishes? The Army was desperate for some form of entertainment after the harsh winter. And Cato‘s themes fit perfectly with those Congress was trying to promote throughout the country. Finally, Washington was a Virginian, and had never known any statewide ban on theatre. The General’s enthusiasm passed down to his officers, who began performing plays of their own once Philadelphia was retaken from the British. Amongst the plays that were planned were those with more salacious themes than Cato such as George Farquhar’s The Recruiting Officer, which satirizes the Army as a simple source of a romantic romp. [13]

Like the Puritans a century before, Congress responded to the army’s defiance by passing a more direct injunction on October 12:

Whereas true religion and good morals are the only solid foundations of public liberty and happiness:

Resolved, That it be, and it is hereby earnestly recommended to the several states, to take the most effectual measures for the encouragement thereof, and for the suppressing of theatrical entertainments, horse racing, gaming, and such other diversions as are productive of idleness, dissipation, and a general depravity of principles and manners.

Resolved, That all officers in the army of the United States, be, and hereby are strictly enjoined to see that the good and wholesome rules provided for the discountenancing of prophaneness and vice, and the preservation of morals among the soldiers, are duly and punctually observed.[14]

This act proved severely ineffective; a harsher injunction punishing performing officers was passed only four days later:

Whereas frequenting play houses and theatrical entertainments has a fatal tendency to divert the minds of the people from a due attention to the means necessary for the defence of their country, and the preservation of their liberties:

Resolved, That any person holding an office under the United States, who shall act, promote, encourage or attend such plays, shall be deemed unworthy to hold such office, and shall be accordingly dismissed.

Yet unlike the previous acts, this one of October 16 did generate substantial opposition. New York Congressman William Duer demanded the vote be published, as a sign of solidarity with the army, showing them who was opposed to their popular pastime. While the act did pass, it was without the support of Georgia, North Carolina, Maryland, Virginia or even New York.[15]

The necessities of the war soon distracted Washington’s Army from theatre until after the Battle of Yorktown. However, negative opinions towards theatre persisted well after the peace, performances in Boston and Philadelphia not receiving official sanction until the 1790s. By that time, however, thanks in part to the American military performances, a greater appreciation of the art from began developing. American plays began being performed in earnest, such as Royall Tyler’s 1787 comedy The Contrast about New York society ladies and William Dunlap’s controversial 1798 analysis of the Benedict Arnold affair, Andre.[16] It is only after the great real life drama of the Revolution and Constitution had concluded that Americans built a strong taste for theatrical drama. But looking around New York today, it is easy to see how well we have made up for lost time!

[1] Continental Congress Association and Peyton Randolph, et al, October 20, 1774, 14 Agreements by Colonies; Printed Broadside, Library of Congress http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=mtj1&fileName=mtj1page001.db&recNum=325

[2] “Pro Patria,” New York Journal, Dec 15, 1774, Readex American HIstorical Newspapers.

[3] James Rivington, A Poor Man’s Advice to his Poor Neighbors (New York: 1774), 9, Eighteenth Century Collections Online [W028936].

[4] Mary V.V. “A Dialogue Between a Southern Delegate and his Spouse on his Return from the Grand Continental Congress” in Norman Philbrick, ed., Trumpets Sounding: Propaganda Plays of the American Revolution (New York: Arno Press, 1976), 38.

[5] “To James Madison from Williarm Bradford, 4 January 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives (http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Madison/01-01-02-0038, ver. 2013-09-28). Source: The Papers of James Madison, vol. 1, 16 March 1751 – 16 December 1779, ed. William T. Hutchinson and William M. E. Rachal (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1962), 131–134.

[6] Andrew O’Shaughnessy, The Men Who Lost America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 132-137.

[7] John Burgoyne, “Prologue for opening the theatre at Boston,” December 1775. Massachusetts Historical Society. http://www.masshist.org/database/viewer.php?item_id=179&img_step=1&mode=dual#page1

[8] John Rushworth, “Historical Collections: September 1642,” Historical Collections of Private Passages of State: Volume 5:1642-45 (1721), 1, British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=80728&strquery=stage playsordinance 1642

[9] C.H. Firth, R.S. Rait (eds), “February 1648: An Ordinance for the utter suppression and abolishing of all Stage-Plays and Interludes, within the Penalties to be inflicted on the Actors and Spectators therein expressed,” Acts and Ordinances of the Interregnum, 1642-1660, 1070-1072. British History Online, http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=56247&strquery=stage playsordinance1642

[10] Including Ann Fairfax Withington, Towards a More Perfect Union: Virtue and the Formation of the American Republics (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); Heather S. Nathans, Early American Theatre From the Revolution to Thomas Jefferson: Into the Hands of the People (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 37; Benjamin H Irvin, Clothed in Rhobes of Sovereignty: The Continental Congress and the People Out of Doors (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 31.

[11] Jared Brown, Theatre in America During the Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 1-5; Peter A. Davis “Puritan Mercantilism and the Politics of Anti-Theatrical Legislation in Colonial America” in The American Stage, Ron Engle and Tice L. Miller, eds. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

[12] Kenneth Silverman, A Cultural History of the American Revolution (New York: T.Y. Cowell, 1976), 94-98.

[13] Brown, Theatre in America, 57-65; Irvin, Clothed in Rhobes of Sovereignty, 221-223.

[14] Journals of the Continental Congress, 12 October 1778. Library of Congress, http://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=lljc&fileName=012/lljc012.db&recNum=142&itemLink=r?ammem/hlaw:@field(DOCID+@lit(jc01236))%230120143&linkText=1

[15] Journals of the Continental Congress, 16 October 1778, Library of Congress.

[16] Jeffrey H. Richards, Early American Drama (New York: Penguin Books, 1997).

5 Comments

Bravo, Dave, a standing O for your article. I’m struck by the contrast between Washington’s and Congress’ attitudes toward theatre. Soldiers who fight and die are more inclined to enjoy their diversions than politicians who think their personal opinions constitute the will of the people. Granted 1776 America saw itself as a moral bulwark against English profligacy, I’d be willing to wager (oops) that Washington saw it as a morale booster worthy of keeping his troops diverted from less pleasant thoughts and activities. In this singular regard, he was not wrong.

Thanks, Steven! There really are a vast array of angles for looking at Theatre in Revolutionary America! You’re right in noting the contrast between Washington and Congress in regards to theatre. In many ways, this contrast speaks to the great difference that already existed between the colonies–and later states–that would never really disappear. Of course, the band on theatre eventually did…

Found this article not only informative but all quite interesting to read about. You have a way of drawing the readers in while teaching them little known facts about our history. Its quite fascinating how congress viewed theatre. Love this article!! Looking forward to reading more from you in the future.

Congrats David!!!!

David, you may want to take a deeper look at the reason why the Puritans sought to ban plays in 1642,